If there is anything anyone knows about Socrates, besides being the great midwife of Western Philosophy, it is that he wrote nothing. I heard it from all of my philosophy teachers and read it in just as many books. “Socrates wrote nothing,” Princeton professor Melissa Lane writes in her exemplary study, Plato’s Progeny: How Plato and Socrates Still Captivate the Modern Mind. “A man who confined himself to oral discussion,” writes Bertrand Russell in his marvelous The History of Western Philosophy. In the best complete works of Plato in English (which I quote throughout this article), its editor John M. Cooper writes in his introduction, “Socrates himself, of course, was not a writer at all.” There are countless others:

“Socrates wrote nothing himself” (W. K. C. Guthrie in his introduction to his translations of Plato’s Protagoras and Meno)

Socrates “wrote nothing” (Penguin’s edition of The Laws)

Socrates was “enigmatic because he wrote nothing himself” (The Oxford Guide to Philosophy)

“Although [Socrates] himself wrote nothing…” (The Cambridge Dictionary Dictionary of Philosophy)

There are several more I could quote from my library alone, saying more or less the same thing. I have read it so many times I do not even bother to question it. In this piece, I do just that, with surprising results and rich suggestion, throwing new light on the dogma that the historical Socrates wrote nothing.

Available Evidence

There are more accurate accounts of Socrates writings than those quoted above: “Socrates left behind no writing,” writes Sir Anthony Kenny in his A New History of Western Philosophy and “no writings of his are extant, if any ever existed,” writes H. N. Fowler in the first volume of Plato in Loeb Classical Library. These formulations are more sober because they state the fact more accurately, namely, none of Socrates writings have come down to us. And to say that he wrote nothing might be an extreme position and probably historically inaccurate given what we know or can know about Socrates.

The chief source we have of Socrates is the Dialogues of Plato (which is epic compared with the other two sources we have in the works of Xenophon and Aristotle). Plato does not try to get away with passing off his Dialogues as an actual historical account, but there is a lot of history in them, least of all the portrayals of contemporaries such as Glaucon and Adeimantus, Plato’s brothers, in the Republic, and Aristophanes and Alcibiades in The Symposium (itself is a piece of historiography for what a drinking party in 5th century B.C.E. Athens might have been like). And of course, it is regular practice in classical scholarship to infer and derive historical facts from the Dialogues, and my doing so here is in keeping with the convention.

Having said that, it is very improbable that Plato would have said of Socrates that he wrote nothing. The evidence he provides can be found the dialogue Phaedo.

Socrates Had a Dream

Phaedo recounts Socrates’ last day in life, not long after he was sentenced to death by an Athenian jury, with hemlock chosen as capital punishment. While awaiting death, Socrates had apparently been writing, and not philosophy but poetry! It is rather surprising: Socrates is notorious for censuring poets and their craft, all throughout Plato’s corpus. Cebes, a disciple of Socrates, asks him about it:

What induced you to write poetry after you came to prison, you who had never composed poetry before, putting the fables of Aesop into verse and composing the hymn to Apollo?

Socrates replies:

I tried to find out the meaning of certain dreams and to satisfy my conscience in case it was this kind of art that they [the dreams] were frequently bidding me to practice.

Dreams here are synonymous with inspiration, prophetic visions, or what the Greeks called a daimon, a kind of semi-divine spirit that counsels one’s conduct. H. N. Fowler’s translation of Phaedo renders the passage this way:

I wished to test the meaning of certain dreams, and to make sure that I was neglecting no duty in case their repeated commands meant that I must cultivate the Muse this way.

Either way, these dreams moved Socrates to make poetry.

We will return to these dreams and what they may signify. For now, Plato here has given us reasons to doubt the dogma.

The Probability that Socrates Wrote

Between the lines, the above passage supplies us with interesting assumptions to investigate:

- Socrates knew how to write poetry, which is why he was able to, though he had “never composed poetry before;”

- Since it is mentioned that he did not specifically write poetry, it could follow that he may have done other forms of writing.

Regarding the first assumption, “never composed poetry before” means Socrates never wrote original poems. This is not the same as saying he never ever wrote poems, period, or that he never learned how write or practice the art. Socrates confirms this later in the passage:

I first wrote in honor of the god of the present festival. After that I realized that a poet, if he is to be a poet, must compose fables….Being no teller of fables myself, I took the stories I knew…and versified the first ones I came across.

Note the casualness with which he claims to have just written verse, as if it comes as no surprise he was able to do so. And it is no small thing, versifying. It takes training and practice to learn. If someone we have known for a long time never composed poems and tells us she just had, our suspicions would be rightly raised if we know that this person did not receive some kind of training early on. That Socrates could have casually claimed to have versified without controversy suggests that Socrates possessed versifying skills.

History may support the assumption. In his comprehensive A History of Philosophy (volume one), Frederick Copleston writes, “Socrates cannot, however, have come from a very poor family, as we find him later serving as a fully-armed hoplite, and he must have been left sufficient patrimony to enable him to undertake such a service.” Thus, since Socrates did not grow up poor, it is then very likely that he received some education, some instruction in writing, as was the case for many of the boys whose families had the means. Plato, for one, is said to have had studied painting and poetry; later he wrote lyrics and tragedies, which Plato himself tells us he threw to the fire to do philosophy. Now, we do not have evidence of this; none of those lyrics or tragedies have come down to us. But anyone who has spent time with his Dialogues can easily perceive that lyric and tragedy was doubtless well within Plato’s range. Just the same—given his awesome reasoning powers, undeniable finesse in deploying myths, frequent visits from daimons—it is also easy to see that writing would have been well within Socrates’ range.

The second assumption is less probable, but perhaps the case of the great tragedian Euripides might offer insight to support it. Many scholars have argued convincingly that there was a working or collaborative relationship between Euripides and Socrates. We know that Euripides was associated with Socrates and was cartooned by comic playwrights like Aristophanes as a disciple of Socrates. Scholars could only speculate as to the nature of their relationship. But one speculation could be that Socrates has contributed to Euripides’ plays, perhaps deepening their philosophical dynamism and subversion of popular wisdom, as a great many of Eurpides’ plays turned out to be. Another interesting speculation, one that would be exciting to pursue, could be the notion that the two were trying their hand at prototype philosophical plays, dialogues one might call them, such that Plato would later go on to master.

This all is very speculative, but that has always been the case when we approach the ancients. At best, however, the speculations presented here give us sufficient insight to undermine, if not do away with altogether, the dogma.

Black Swans, End Scene

There is something else very interesting about the passage above from Phaedo. Before death, Socrates was having doubts about whether he should have been practicing philosophy in the first place. After explaining how his dreams led him to versify Apollo and Aesop, he describes them:

The same dream often came to me in the past, now in one shape, now in another, but saying the same thing: ‘Socrates,’ it said, ‘practice and cultivate the arts.’ In the past I imagined it was instructing and advising me to do what I was doing…to practice the art of philosophy, this being the highest kind of art.

In other words, his daimon, all his life, had been telling him to develop the “arts,” which all along he thought was philosophy, the best kind. Near death though, his “conscience” was telling him that he might have been mistaken about the art his dreams were telling him to practice. “I thought it safer not to leave here until I had satisfied my conscience by writing poems in the obedience to the dream,” Socrates says as the main reason for having uncharacteristically written verse. Imagine that! What would have happened to Western Philosophy had Socrates interpreted his dreams to mean do poetry not philosophy?! There would have been no Plato, and therefore no Aristotle.

What is also interesting in this brief scene is the ghost of Aesop present in Socrates’ prison cell in those last days. They have so much in common it is erie. They are both legends whose ultimate natures we will never know since we only know them through the accounts of others. They are both freaks of nature, ugly ducklings by universal accounts. And they are both notoriously wise, known to embarrass and provoke and annoy those who engage them. According to the apocryphal Life of Aesop, Aesop incurred so much wrath from the citizens of Delphi that they executed him by throwing him off a cliff. Whereas for Socrates, his cliff is the hemlock, from the citizens of Athens, for roughly the same offense. Again, erie. Of course, both did not leave us with any of their writings.

But to say that these black swans of history were not writers of sorts, or that they never ever wrote, just does not seem right. The notion is inconsistent with their shrewd way with words, gifts for fable- and myth-making, storytelling, wisdom, and their unmatched capacity to arrest and animate the imagination. These are qualities we would today commonly assign to a writer. These two—at once historical and mythic and fictional—gave us stories and ideas that would unfurl and erect forests of books and refuges for the mind, sprung from all corners of the world, up to the present day, this article notwithstanding, and with no conceivable end in influence and inspiration in sight. Socrates and Aesop wrote orally, their preferred form of publication. It is a dogma to assume they never did write. It is time for us to question it. Socrates would have wanted us to.

FURTHER and SUGGESTED READING

Plato: Complete Works (1997) edited by John M. Cooper, Hackett Publishing Company

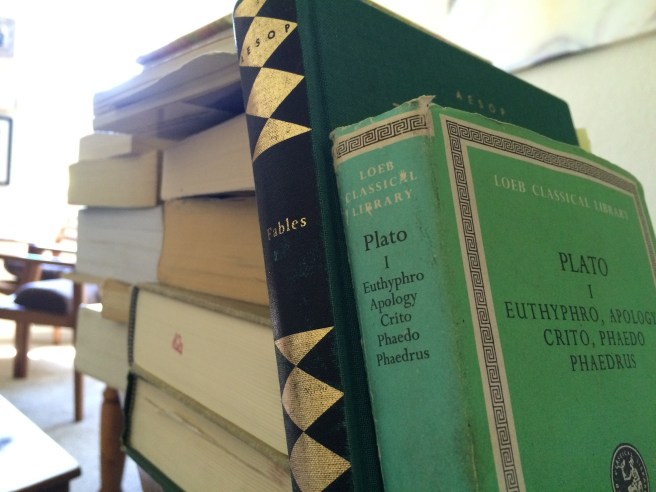

Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Phaedrus translated by Harold North Fowler for the Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press

Plato Progeny: How Plato and Socrates Still Captivate the Modern Mind by Melissa Lane, Classical Inter/Faces

The History of Western Philosophy (1967) by Bertrand Russell, Touchstone and Simon & Schuster

A History of Western Philosophy (2010) by Sir Anthony Kenny, Oxford University Press (this one is particularly highly recommended)

A History of Philosophy, Volume I: Greece and Rome (1993) by Frederick Copleston, S.J., Image Books

Aesop’s Fables (2002) translated and edited by Laura Gibbs, Oxford University Press

You must be logged in to post a comment.